Crispy Kelp

If you like potato chips, fried kelp might be a good healthy alternative!

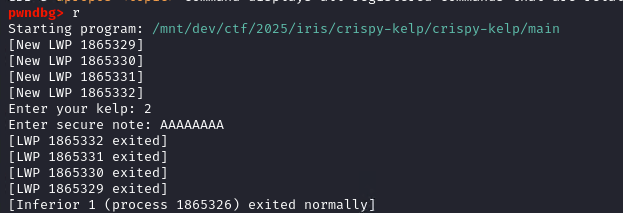

This is a Go binary that takes as input a number and a string and encodes the string into a file.

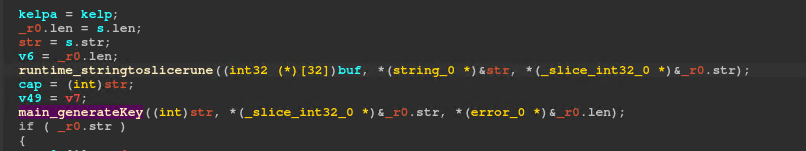

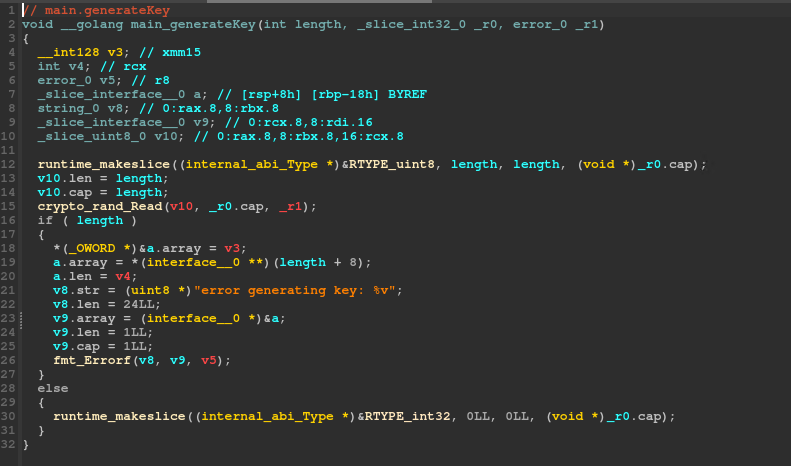

It generates a key:

The decompiled Go code is really hard to read, it’s much easier to analyze it dynamically.

Let’s put a breakpoint before calling generateKey.

For kelp, I used the value 32, and the string is the letter A repeated 16 times. This is to have values that stand out for kelp and input length when we find them in arguments.

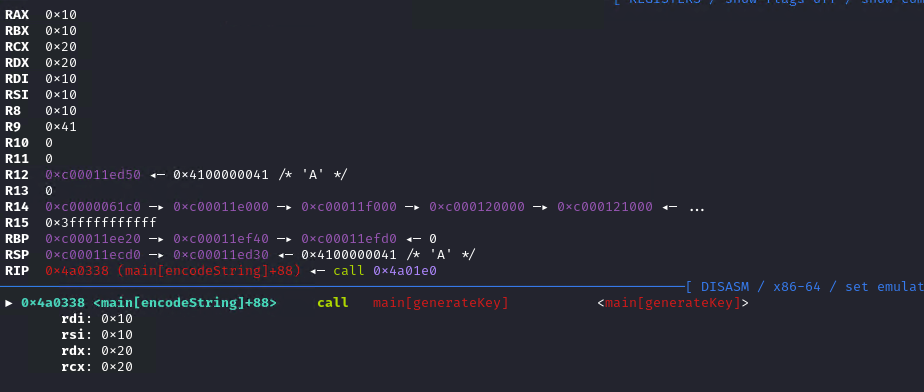

generateKey is called with 0x10 as a parameter, which is the input length. So we can assume that the key has the same length as the input. The value of 0x20 (kelp) is also present in the potential parameters, but it’s probably a coincidence, since it’s just at the 3rd and 4th parameter. The function is pretty simple and only generates random values using the crypto package.

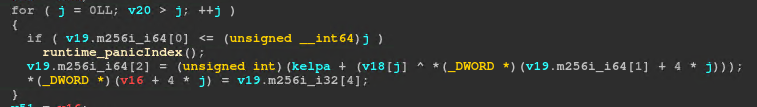

We see two loops that stand out due to the usage of the xor operator. Let’s take them one by one.

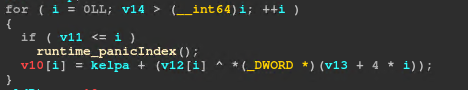

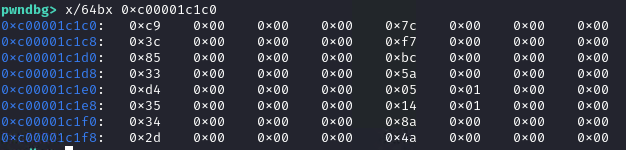

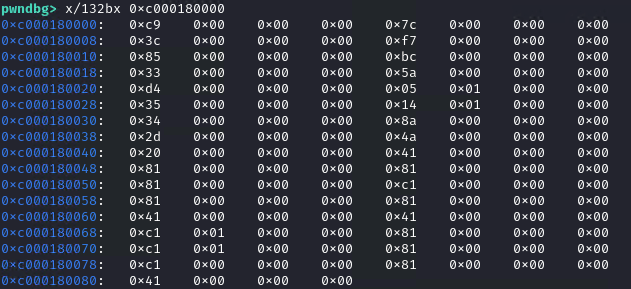

Before placing a breakpoint here, let’s take note of the random values returned by generateKey. The buffer is in RAX after the call.

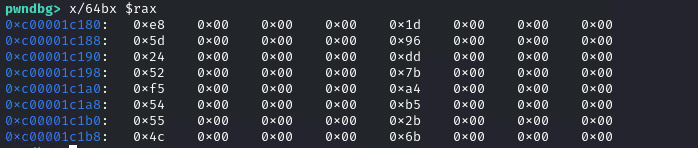

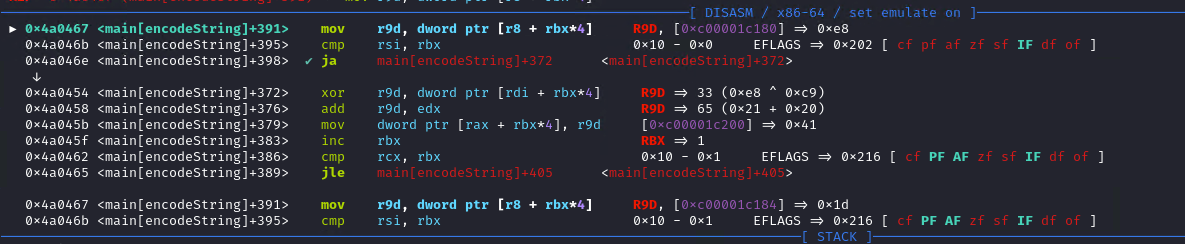

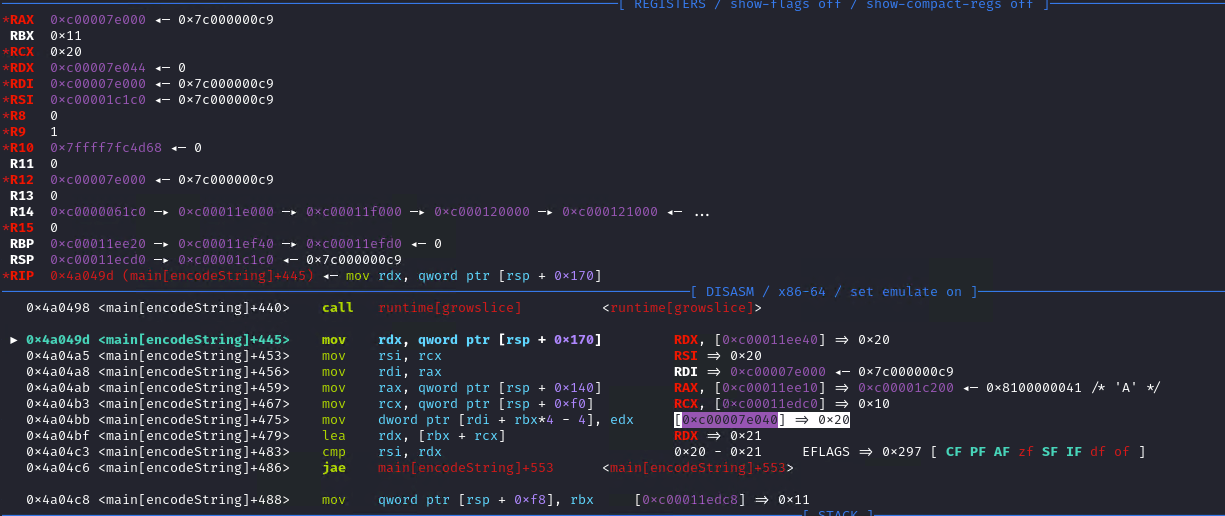

We see that the values are returned as dwords instead of bytes. Now let’s place a breakpoint in the for loop, before the time of an assignment in the buffer.

Pwndbg is really cool and shows us the values before the instructions are even executed. It executes a XOR operation between 0x41 (first byte of our input) and 0xe8 (first random value). Then, it adds 0x20 (kelp). This is equivalent to the following pseudocode:

1

2

for i in range(len(input_)):

output1[i] = (input_[i] ^ random_[i]) + kelp

Let’s note the buffer address (written in purple at the third instruction), because we want to know the values after this loop. We also want to analyze the second for loop:

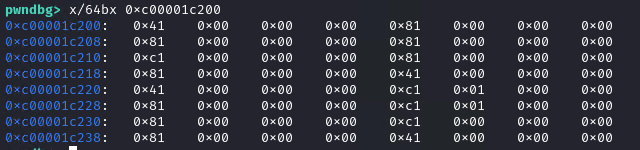

Let’s place a breakpoint there and when we hit the breakpoint we also want to dump the values from the first loop.

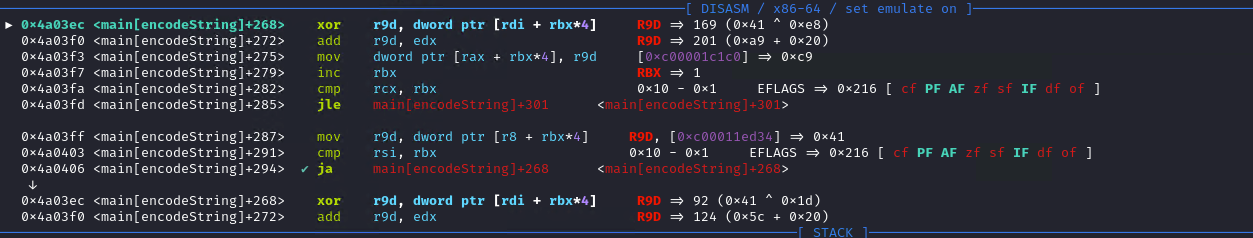

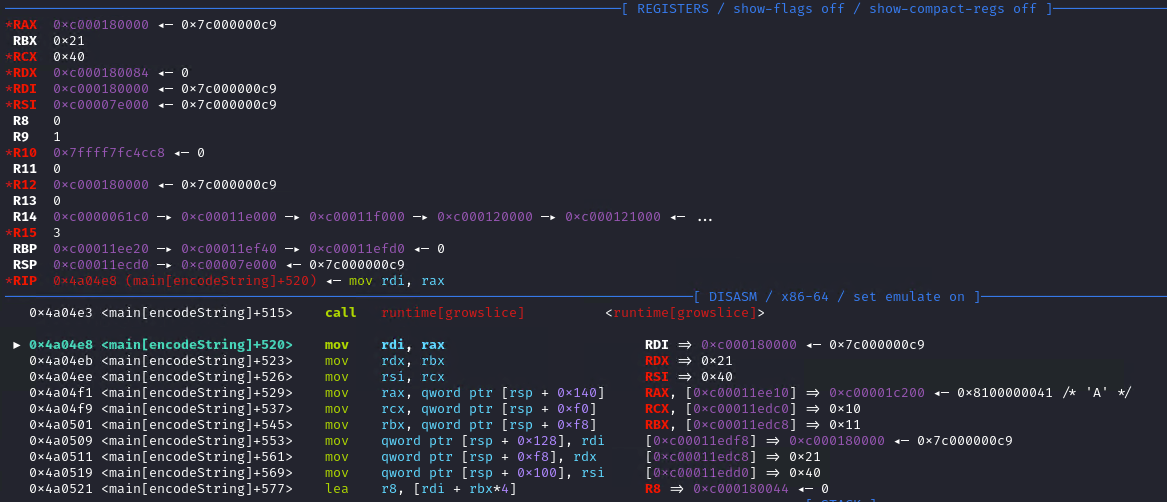

Now, let’s analyze the second loop.

It executes a XOR between 0xe8 (first random value) and 0xc9 (first value of output1) and adds 0x20 (kelp). The equivalent in pseudocode is:

1

2

for i in range(len(input_)):

output2[i] = (output1[i] ^ random_[i]) + kelp

Let’s note the buffer address again and get the values after the loop:

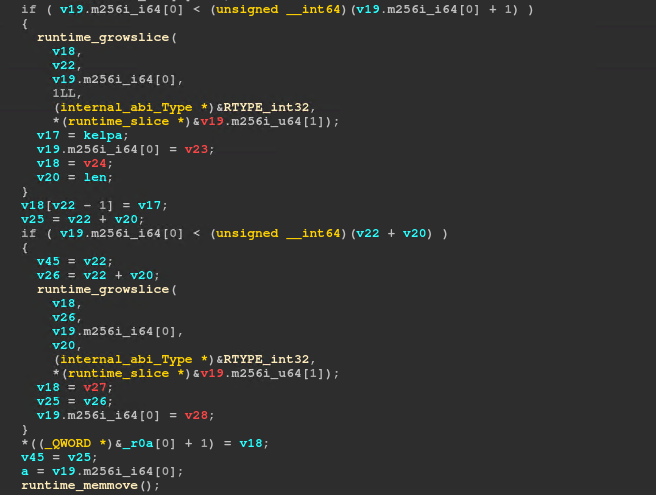

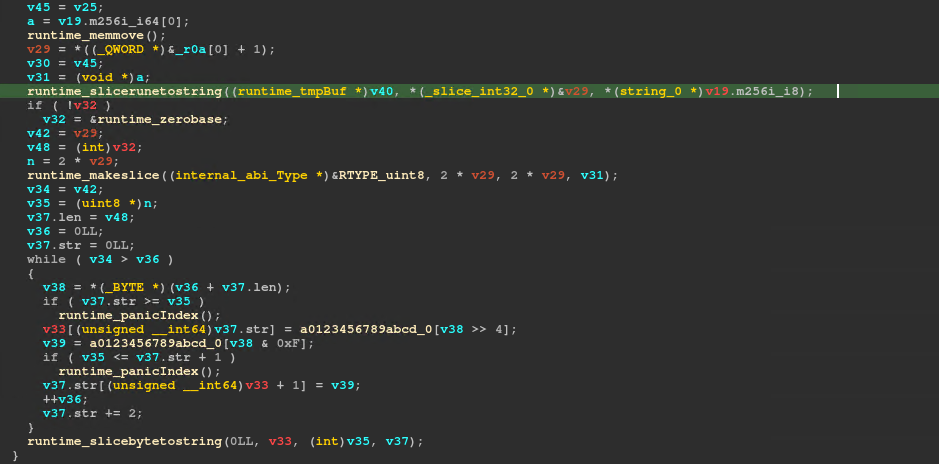

After these two loops we have 2 calls to runtime_growslice, which is called when Go wants to make a slice bigger. Typically, this is used to add values into the array. This is followed by a call to runtime_memmove, which is called when Go wants to move some memory around. Given that it comes after growing the slice, most probably it extends the slice with values from another slice.

Let’s put a breakpoint at the first call, note the buffer returned in RAX and see what happens in the following instructions:

At offset 0x40 of the buffer (length of our input times 4, since we are working with dwords), the value of kelp is written.

Let’s do the same for the second call.

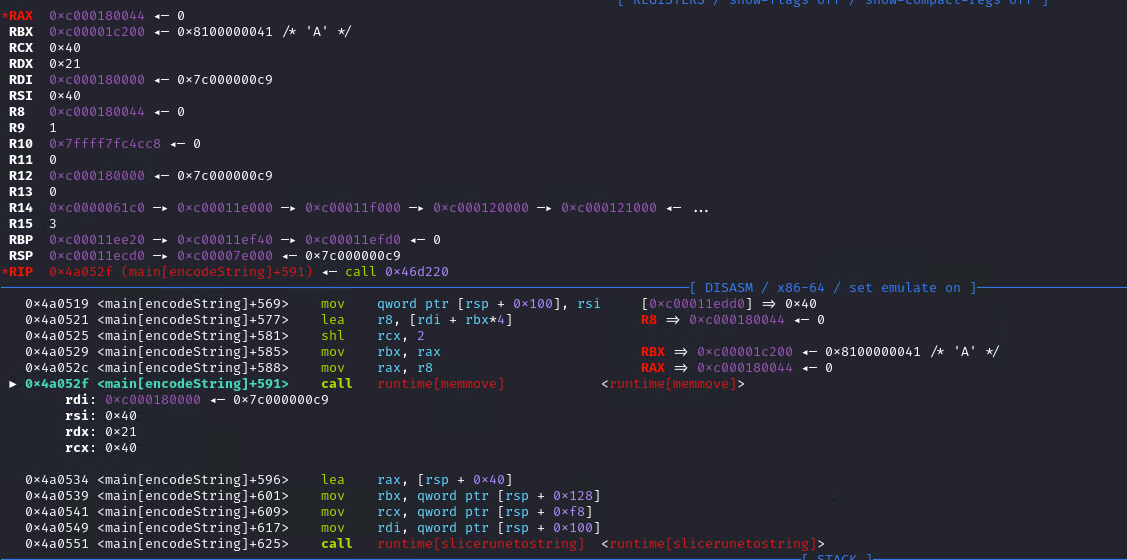

Nothing interesting happens in the following instructions, but we can go until the call to runtime_memmove.

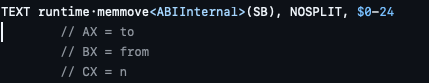

We can see that the first argument is the slice grown earlier. But, looking at the source code of the function, the arguments do not follow the expected calling convention:

The destination is the first slice that was grown (output1 + kelp). The source is output2. We can check the result after the call:

The final buffer is output1 + kelp + output2.

After this, the binary calls one more function, encodes the result to hex and writes it to kelpfile.

runtime_slicerunetostring is called when the string() function is called on a rune slice. A rune is a dword value in Go, usually used for Unicode characters. Its inverse is calling []rune() on the string.

We have all pieces of information we need. We have to decode from hex, convert to a rune slice, separate the 2 outputs and kelp and inverse the 2 formulas.

Let’s recall the 2 formulas:

1

2

for i in range(len(input_)):

output1[i] = (input_[i] ^ random_[i]) + kelp

1

2

for i in range(len(input_)):

output2[i] = (output1[i] ^ random_[i]) + kelp

From the second one we can compute the random values, and then from the first one we can compute the original input.

Converting the string-to-rune function in Python is pretty complicated, so we can just write the exploit in Go.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

package main

import (

"fmt"

"os"

"encoding/hex"

)

func main() {

hexString, err := os.ReadFile("kelpfile_original")

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

bytes, err := hex.DecodeString(string(hexString))

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

runes := []rune(string(bytes))

runesCount := len(runes)

fmt.Printf("Total count: %d\n", runesCount)

output1 := runes[:(runesCount / 2)]

fmt.Printf("Output 1 length: %d\n", len(output1))

kelp := runes[runesCount / 2]

fmt.Printf("Kelp: %d\n", kelp)

output2 := runes[(runesCount / 2 + 1):]

fmt.Printf("Output 2 length: %d\n", len(output2))

random := make([]rune, runesCount / 2)

for i := 0; i < runesCount / 2; i += 1 {

random[i] = (output2[i] - kelp) ^ output1[i]

}

input := make([]rune, runesCount / 2)

for i := 0; i < runesCount / 2; i += 1 {

input[i] = (output1[i] - kelp) ^ random[i]

}

fmt.Println(string(input))

}